President Donald Trump’s August 1 deadline for new global trade agreements has plunged international commerce into what experts describe as “total, random chaos.” Rather than fostering stable economic relationships, the administration’s aggressive stance, marked by new tariff threats against nations like India and Brazil, has created widespread uncertainty. This volatile approach challenges conventional trade norms and raises significant questions about the true objectives and outcomes of current U.S. trade policy.

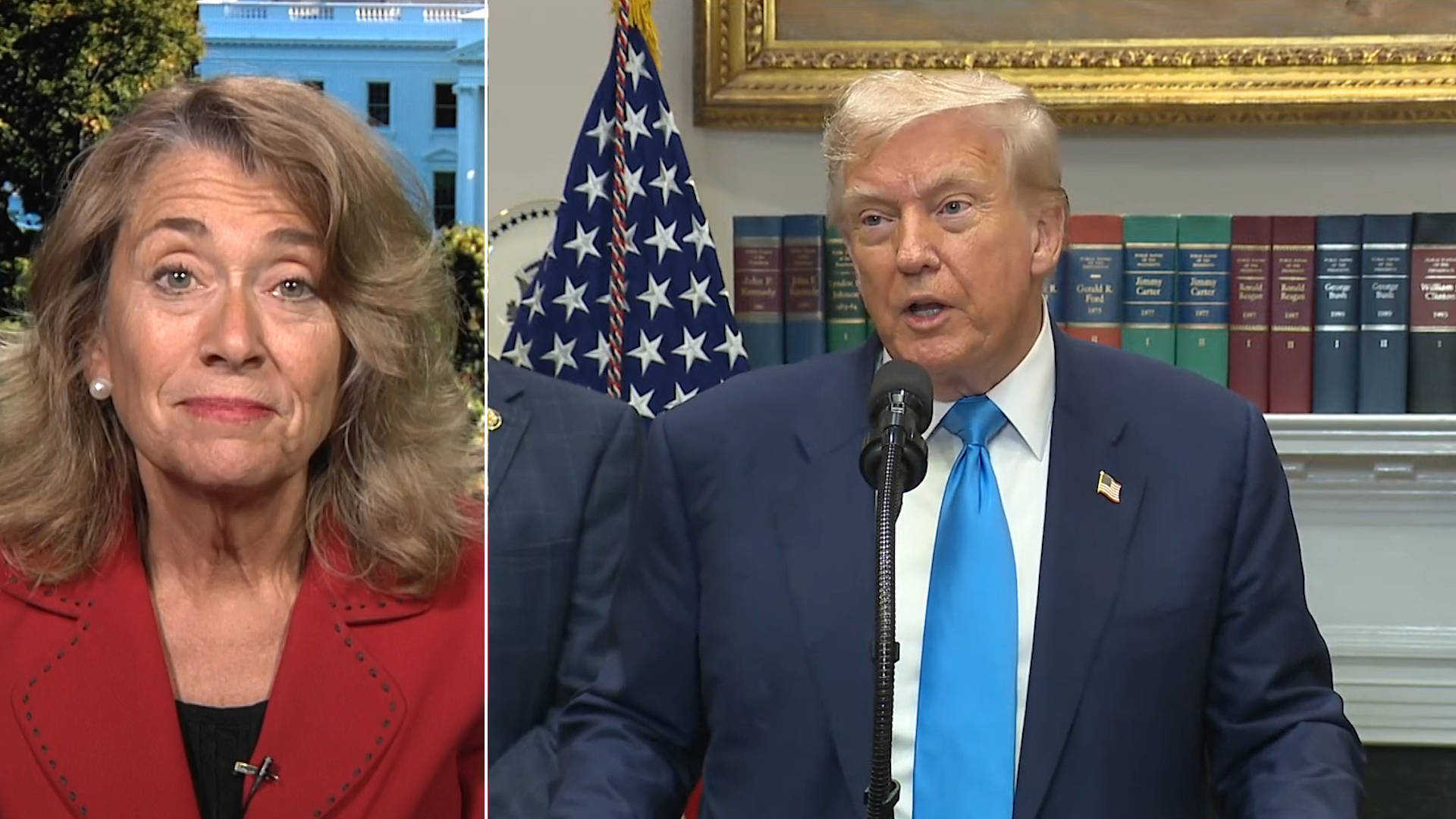

According to Lori Wallach, director of the Rethink Trade program at the American Economic Liberties Project, the Trump administration’s deployment of tariffs constitutes an “abuse of the tariff tool,” often driven by unpredictable foreign policy whims rather than a coherent strategy. Wallach emphasizes that these actions deviate sharply from the promised goal of rebalancing U.S. trade and rebuilding domestic manufacturing, contributing instead to a landscape of economic unpredictability.

The erratic nature of trade announcements—on one day, off the next—is actively chilling investment across various sectors. New factory constructions, initiated under previous administrations, have reportedly slowed or halted, as businesses face immense uncertainty regarding future trade conditions. This instability undermines long-term economic planning and contradicts the stated objectives of strengthening American industry through strategic trade policies.

Further analysis reveals that many of the touted trade deals, often unwritten and vague, appear to prioritize specific corporate interests rather than broad economic benefit. Demands for Big Tech include dismantling other countries’ anti-monopoly rules, while Big Pharma seeks to elevate medicine prices, and Big Oil aims for increased U.S. carbon-based fuel purchases. This suggests a pattern where trade agreements serve particular constituencies rather than a comprehensive national economic agenda.

Illustrating the inconsistent application of tariffs, the U.S. imposed a 50% tariff on Brazil, despite maintaining a trade surplus with the South American nation. Such decisions, seemingly based on political grievances rather than economic rationale, undermine the stated goal of balancing trade. Similarly, new agreements with the European Union, Japan, and South Korea, which roll back existing tariffs on imported vehicles, have been criticized for failing to demand higher wages or labor rights in low-wage supply chains, thereby disadvantaging domestic auto production.

The United Auto Workers (UAW) has vehemently condemned these recent trade deals, particularly the agreement with Japan, asserting that “American workers are once again being left behind.” The union argues that such agreements reward transnational automakers relying on “low-road labor practices,” including substandard wages and union-busting tactics, advocating instead for trade policies that elevate standards rather than promoting a “race to the bottom.” This strong opposition highlights significant concerns within the American labor sector regarding the true impact of these new trade deals.

A critical question surrounding tariffs is who ultimately bears the cost. Contrary to popular belief that foreign governments or American consumers solely pay, data suggests a more nuanced reality. Many foreign companies, eager to maintain access to the lucrative U.S. market, often absorb or split the tariff costs with American importers. While U.S. companies may sometimes engage in price gouging, the direct cost of the tariff itself is frequently managed by the foreign exporter, with the revenue going to the U.S. Treasury, challenging simplistic notions of tariff burden.

Ultimately, a truly effective U.S. trade policy must transcend mere political whims and align with broader industrial strategies. To genuinely rebalance the trillion-dollar trade deficit, rebuild manufacturing, and foster supply chain resilience, a comprehensive approach is required. This involves using tariffs strategically as part of a larger toolkit, ensuring that trade actions contribute to creating good jobs, enhancing national security, and mitigating global challenges, moving beyond the current “abuse of the tariff tool” towards more sustainable economic outcomes.

Leave a Reply